For people, inheriting the family silver can be a mixed blessing, depending on your feelings regarding elderly cutlery or dinnerware. Horses have it easier: they don’t have any cutlery at all, and inheriting the family silver often means they have unusual – and absolutely stunning – coat colours.

When a horse or pony inherits either one or two copies of a rare version of the PMEL17 gene (melanocyte 17 precursor gene) known as silver, it alters the production of black pigment in their coat in an analogous manner to the way cream alters the production of red pigment. The mane and tail of the horse become a cream or silver colour, while the short hair on the body is only slightly affected. Simple concept, amazing result.

As I’ve said in all these horse genetics articles, the important things to remember when discussing genes are:

- Your horse has two copies of each gene*, one inherited from either parent;

- There are many different versions of each gene in the horse population, some of which can produce identical or nearly identical appearance and biological function, while other versions can produce a different coat colour or cause disease; and

- Each physical characteristic of your horse, including coat colour, results from the combined effects of the two copies of each gene, AND the interactions between a large number of different genes.

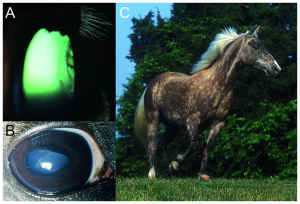

A) Single or multiloculated cysts originating from the ciliary body, iris and occasionally extending into the retina in the temporal quadrant of the eye is the hallmark of the Cyst phenotype and frequently observed in horses with the MCOA phenotype. However, in the MCOA phenotype, other intraocular anomalies, such as cataracts and mitotic pupils, may block the view of the temporal part of the posterior chamber and peripheral retina. B) The right eye of a Rocky Mountain Horse with ectropion uvea, dyscoria, cataract, and lens subluxation. The granula iridica is hypoplastic, the pupil is misshapen, and circumferential ectropion uvea is present. Nuclear cataract of the nuclearcortical junction is present. Vitreous is present in the anterior chamber between the iris and lens secondary to posterior ventral lens subluxation. C) A shiny white mane and tail, in conjunction with a slightly diluted body color with dapples, is typical of a genetically black Silver colored horse. This horse has also been diagnosed with MCOA. Reprinted from Andersson et al., BMC Genetics 2008, 9:88.

In this case, it’s important to remember that the versions of the PMEL17 gene known as silver interact with the basic coat colour genes. When the basic coat colour is black and a silver gene is present, the horse or pony will be black silver (also called silver dapple): a cream or white mane and tail with a dark grey or dark chocolately brown body that generally has strong dappling patterns. When the basic coat colour is bay/brown, the horse or pony will be bay silver: the rich red body of a bay with a creamy mane and tale, as you can see on Kelsie Park Mirinda above.

So far, so good, or at least so gorgeous.

The tricky bit is that when silver interacts with a basic coat colour of chestnut, you get chestnut. “What?”, I hear you say. But yes, it’s true: with no black pigment to act on, there is no change to the colour. Chestnut plus silver equals chestnut. The family silver hasn’t exactly been stolen though, just hidden. A chestnut with the silver gene can pass it on to their own foals.

So is there any difference in appearance between a horse or pony with one copy of the silver gene and one with two copies? I can’t find anything definitive, but image searches suggest that there is no obvious difference. If you want to know, genetic testing would be the quickest way to find out.

The beautiful silver coat colour comes with a flip-side: Multiple Congenital Ocular Anomalies (MCOA) syndrome. A scientific paper published in 2013 by a team of researchers in Sweden concluded that it’s not a coincidence that silver horses are often diagnosed with MCOA, because the same mutation that causes that beautiful silver coat also causes these malformations of the eyes. (Thank-you for your good work Lisa S. Andersson, Maria Wilbe, Agnese Viluma, Gus Cothran, Björn Ekesten, Susan Ewart, and Gabriella Lindgren.)

For horses that inherited one copy of the silver gene, the most common eye abnormality is cysts within the eye. These generally don’t cause noticeable vision problems, and there is no indication of that the condition is painful. The cysts can run along or between various structures in the eye (some can be seen on the right side of the eye in Part A of the illustration above). In rare instances, these horses can have retinal detachment or other retinal abnormalities that appear result from continuation of cysts into the retina. This is very likely to affect the horse’s vision. If you think this may be the case for your silver horse (remembering horses with the silver gene can be chestnut too), your vet should be able to confirm it for you. The management guidelines for appaloosa horses with night blindness have some good ideas for dealing with horses with poor vision in low light.

Horses that have inherited two copies of the silver gene (i.e. one from each parent) generally have much more severe forms of MCOA, although their vision can still be OK. The list of eye abnormalities that can occur for these horses is extensive, including cataracts, misshapen and/or non-responsive irises, misshapen and enlarged cornea (see the bulging eye of the mare pictured above), as well as cysts that are generally more extensive and numerous than for horses with a single copy of the gene. However no single horse is likely to have all these abnormalities at once, and their effect on the horse’s vision can be widely variable.

All of these eye abnormalities develop before birth. There is also a lot of variation between horses (and between ponies) with regards to how many abnormalities there are, and how they affect the horse’s vision. This can give people wanting to own a silver horse or pony (I’d include myself in this category!) some confidence: if you are happy with the horse’s performance and vision in a pre-purchase test or examination, the nature of this syndrome means that it is unlikely to progress.

If you are a breeder of silver horses, please consider the severity of eye problems that can come with two copies of the silver gene. I would recommend against breeding a silver horse or pony to another silver – although the risk isn’t huge, there is a chance of producing a foal with such poor vision that it will cause heartache and expense wherever it goes.

Do you want to know if your horse has one or two copies of the silver gene? At Practical Horse Genetics we are currently working to add this test to our repertoire and it should be available shortly.

* Except for genes on the X and Y chromosomes in male horses, where there may be only one copy.